I. A Call Beyond Borders

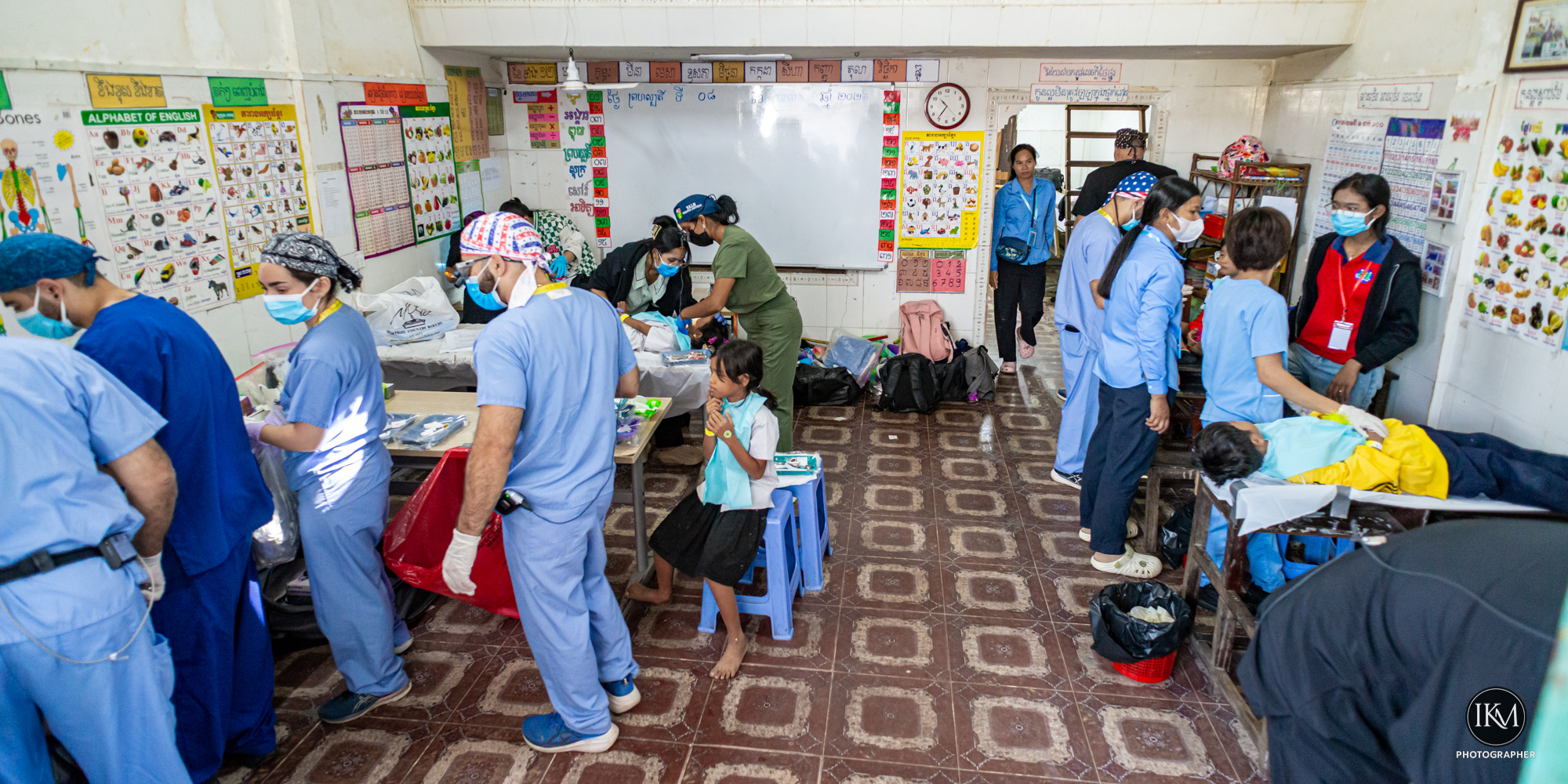

Every year, dentists, dental students, and young adults pack their bags and travel thousands of miles to join Kids International Dental Services (KIDS) missions. They arrive in Cambodia, the Philippines, or other underserved regions not for profit, but for purpose.

The question is simple: why do they come? The answer is layered — a mix of compassion, professional growth, and the search for meaning.

II. Compassion in Action

For many volunteers, the motivation begins with empathy. They know that untreated dental pain can rob a child of sleep, appetite, and education.

- Immediate impact: A single extraction can end months of suffering.

- Visible change: Volunteers witness children smile freely for the first time in years.

- Human connection: Holding a child’s hand during treatment, they feel the bond of shared humanity.

As one volunteer explained: “Dental pain steals childhood. If I can give back even one night of peaceful sleep, it’s worth everything.”

III. Professional Growth

KIDS missions are also a proving ground for young professionals.

- Hands‑on experience: Dental students gain practical skills in challenging environments.

- Adaptability: Working without the comforts of modern clinics teaches resilience and creativity.

- Mentorship: Experienced dentists guide students, creating a cycle of service that continues long after the mission ends.

For many, these missions shape their careers. They return home not just as better clinicians, but as advocates for global health.

IV. The Search for Meaning

Beyond skill and service, volunteers often describe a deeper pull.

- Perspective: Witnessing poverty and resilience reframes their own lives.

- Purpose: Missions remind them why they chose dentistry — not just to treat teeth, but to care for people.

- Community: Volunteers form bonds with each other, united by shared challenges and triumphs.

The experience becomes more than a trip; it becomes a chapter in their personal story of meaning and responsibility.

V. Challenges They Embrace

Volunteers face long days, relentless heat, and limited resources. Yet these challenges are part of the appeal.

- They learn to improvise when equipment falters.

- They discover patience when children are afraid.

- They find joy in small victories — a child’s laughter, a parent’s gratitude, a smile restored.

VI. Why They Keep Coming Back

Many volunteers return year after year. They speak of unfinished work, of children they want to see again, of communities that feel like family.

KIDS missions are not just about dentistry. They are about dignity, education, and hope. Volunteers come because they believe in those values — and because they see them come alive in every courtyard clinic, every classroom turned into a dental station, every child who walks home pain‑free.

✨ Conclusion

The volunteers of Kids International Dental Services come for compassion, for growth, and for meaning. They leave with stories, skills, and a renewed sense of purpose.

In Cambodia and beyond, their presence is proof that service is not just about what you give — it’s about what you discover when you step into someone else’s world, hold their hand, and help them smile again.

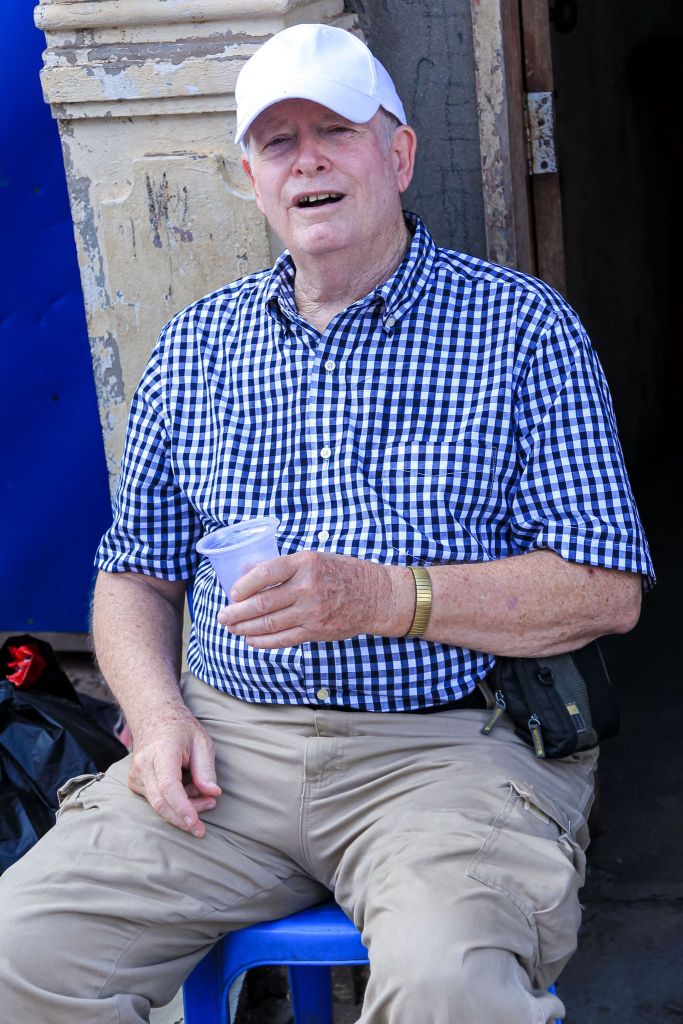

Big thanks go out to David for his master class in organisation and also to Jon and Jamie whose hard work keeps this thing going, as well as the none dental volunteers and local interpreters.