🧑🎨 Early Life

- Born: June 15, 1933, in East London, to Irish immigrant parents.

- World War II: Evacuated twice as a child — first to Kings Langley, where he lived briefly with actors Roger Livesey and Ursula Jeans, and later to Wales.

- Education: Initially studied painting at St. Martin’s School of Art, but switched to dress design. His design background gave him a sharp eye for form and style, which later influenced his photography.

Brian Duffy (1933–2010) was a groundbreaking British photographer and film producer, best known for his fashion and portrait work during the 1960s and 1970s. Alongside David Bailey and Terence Donovan, he formed the “Black Trinity” of photographers who revolutionized fashion imagery, bringing a raw, street‑wise energy that defined Swinging London.

📷 Career Beginnings

- Started as a fashion illustrator for Harper’s Bazaar.

- Transitioned to photography in the late 1950s, securing a position at British Vogue in 1959.

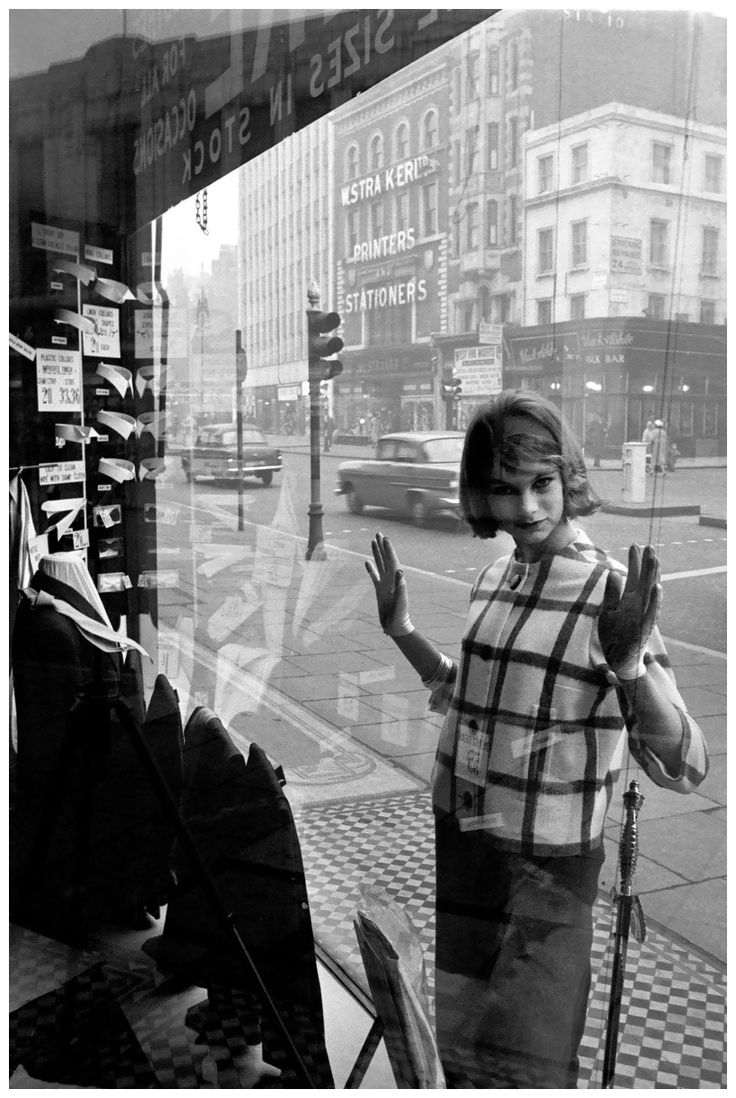

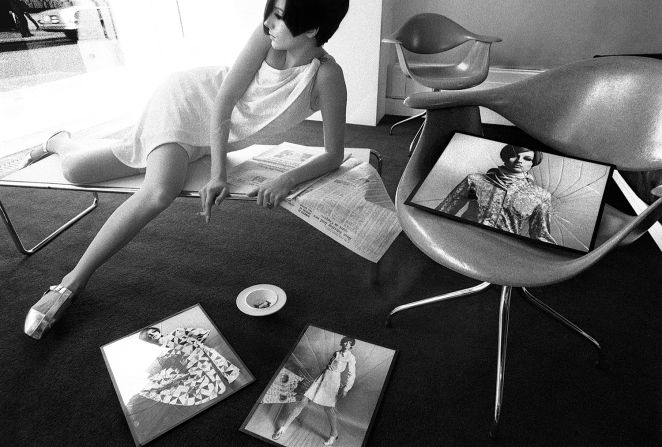

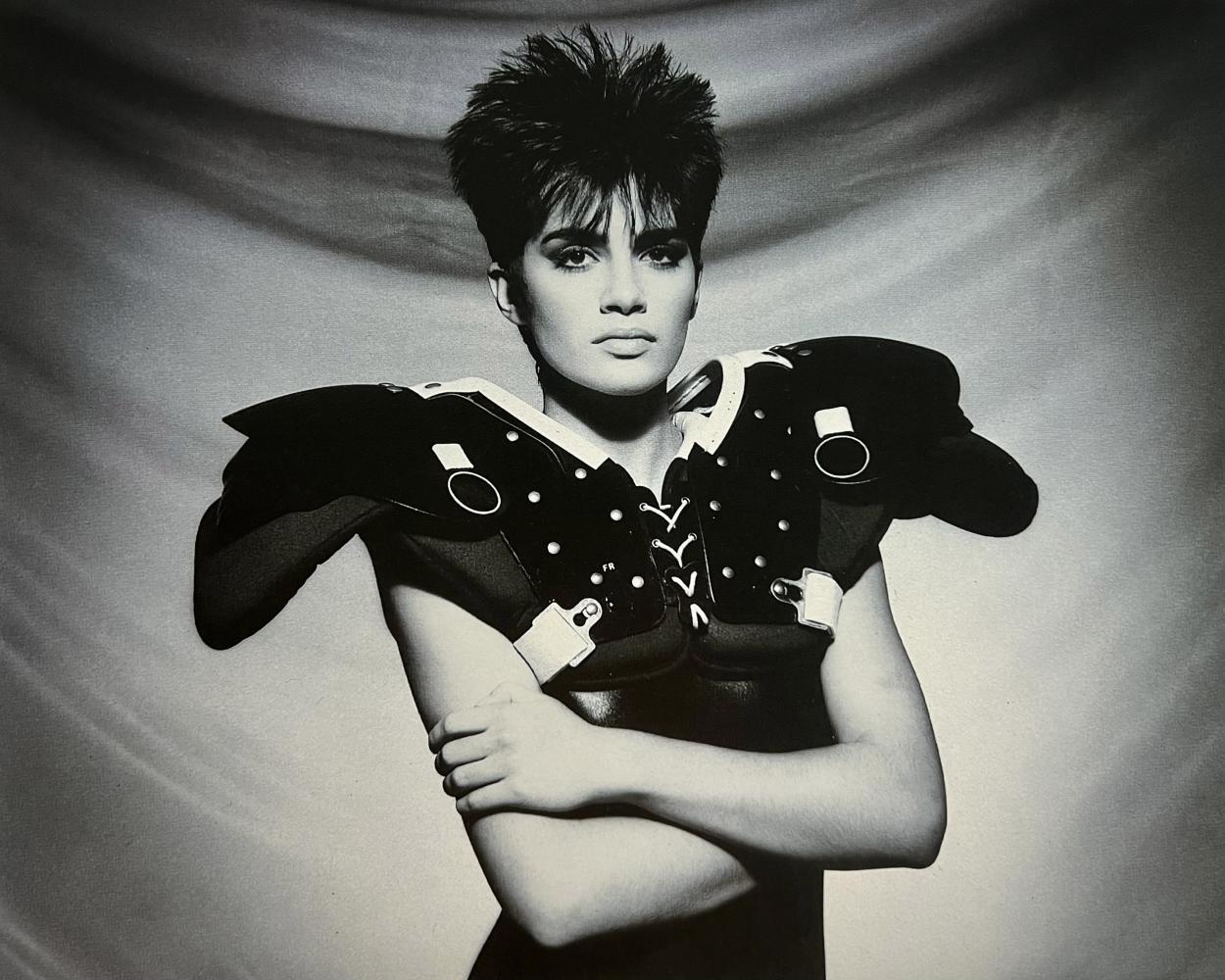

- His unconventional approach — using natural light, dynamic poses, and urban settings — broke away from the stiff, aristocratic fashion imagery of the time.

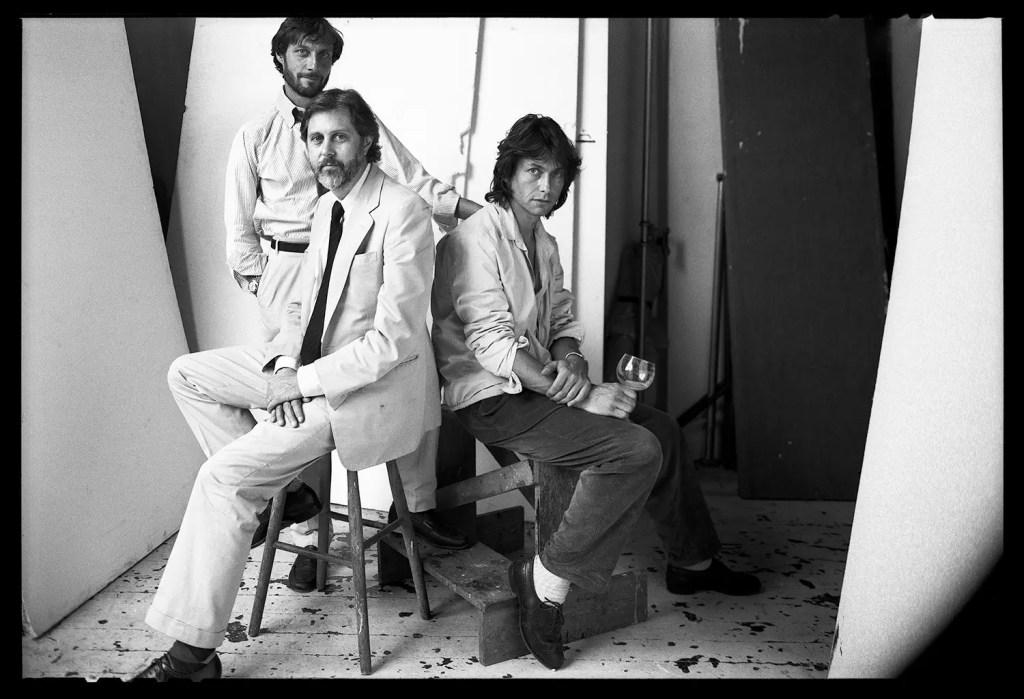

🌟 The “Black Trinity”

- Alongside David Bailey and Terence Donovan, Duffy formed the so‑called “Black Trinity.”

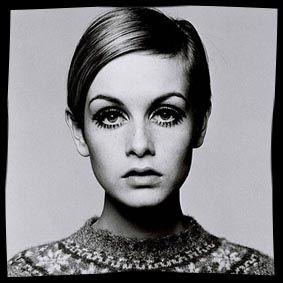

- Together, they democratized fashion photography, capturing the energy of Swinging London and making models look like cultural icons rather than distant aristocrats.

- Their work mirrored the youth revolution of the 1960s, blending fashion with street culture.

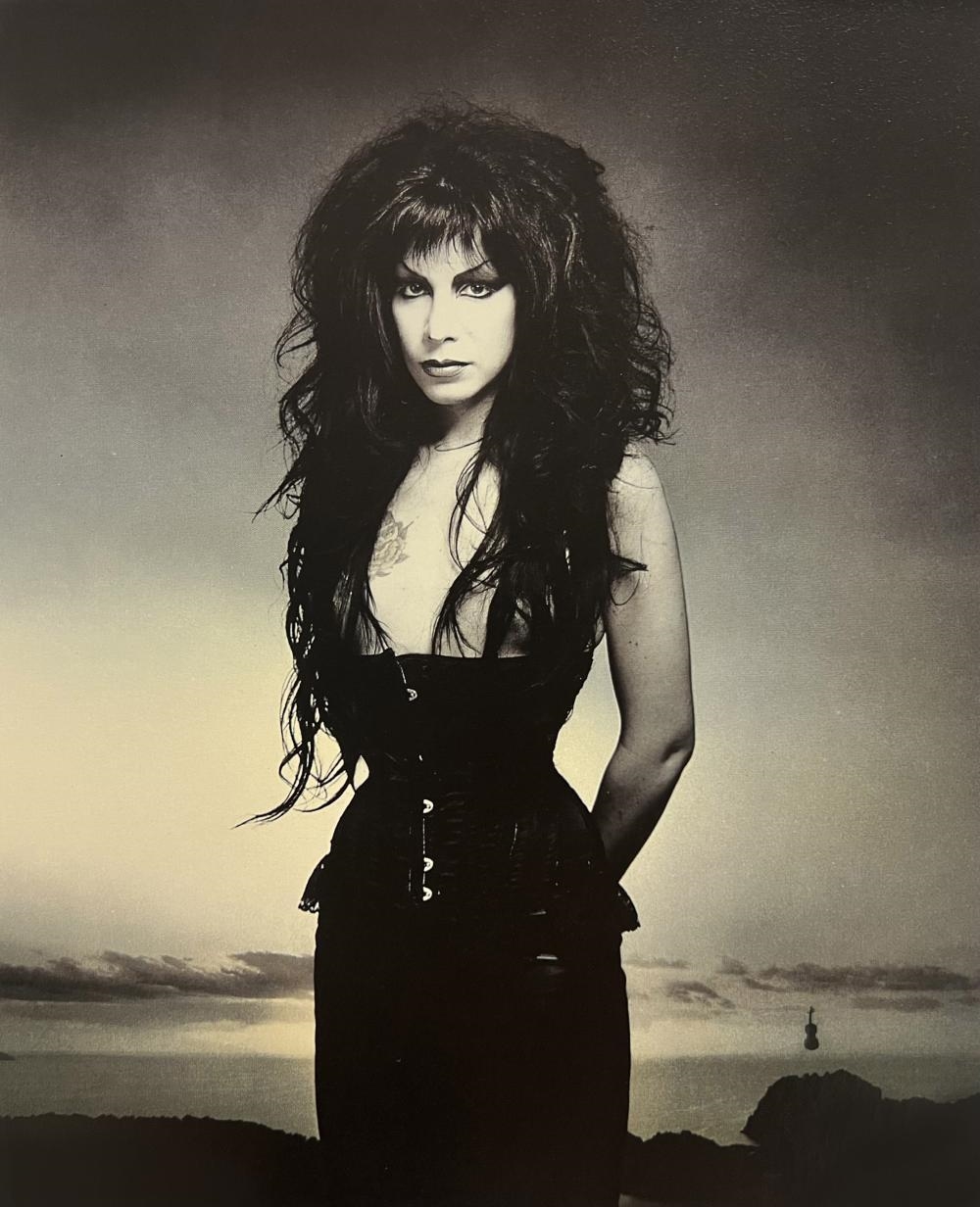

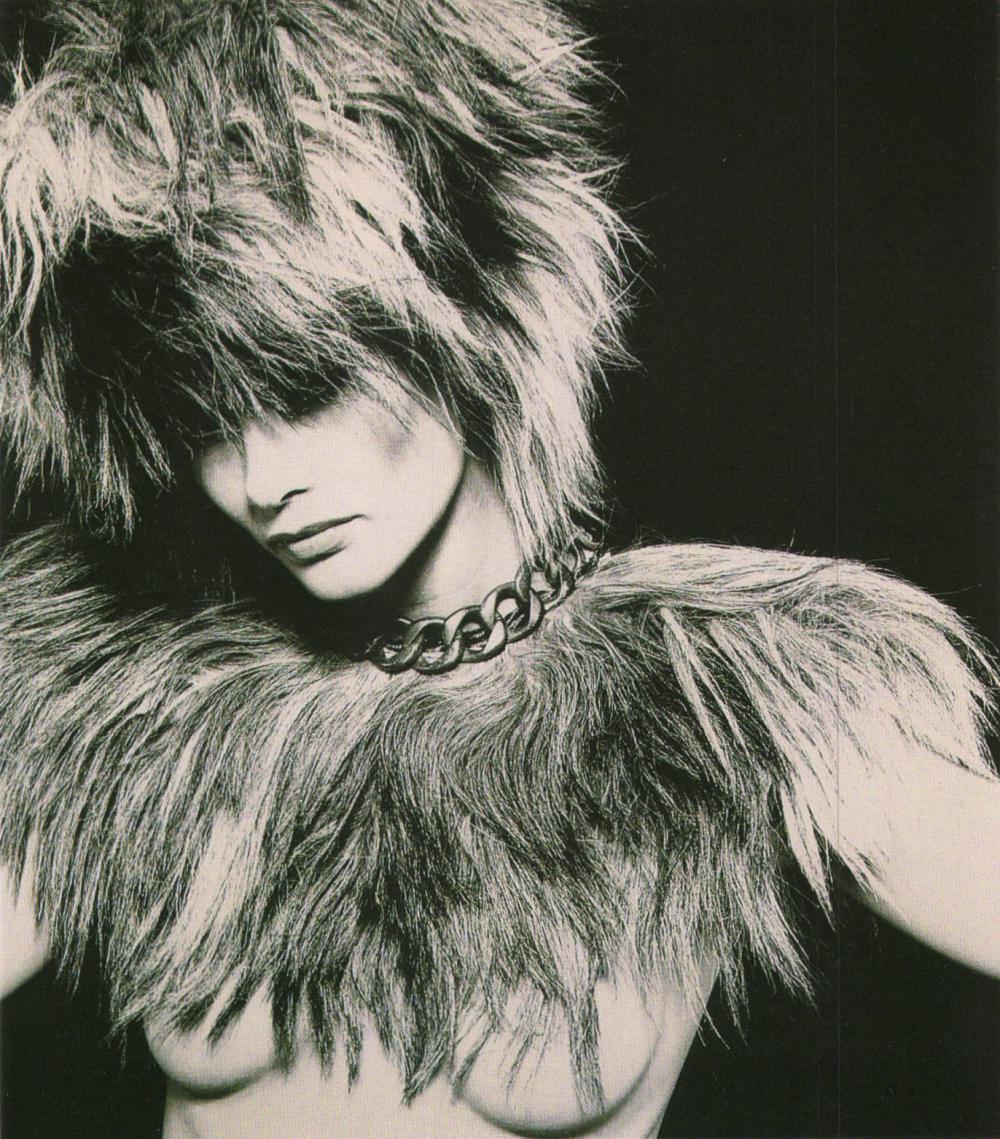

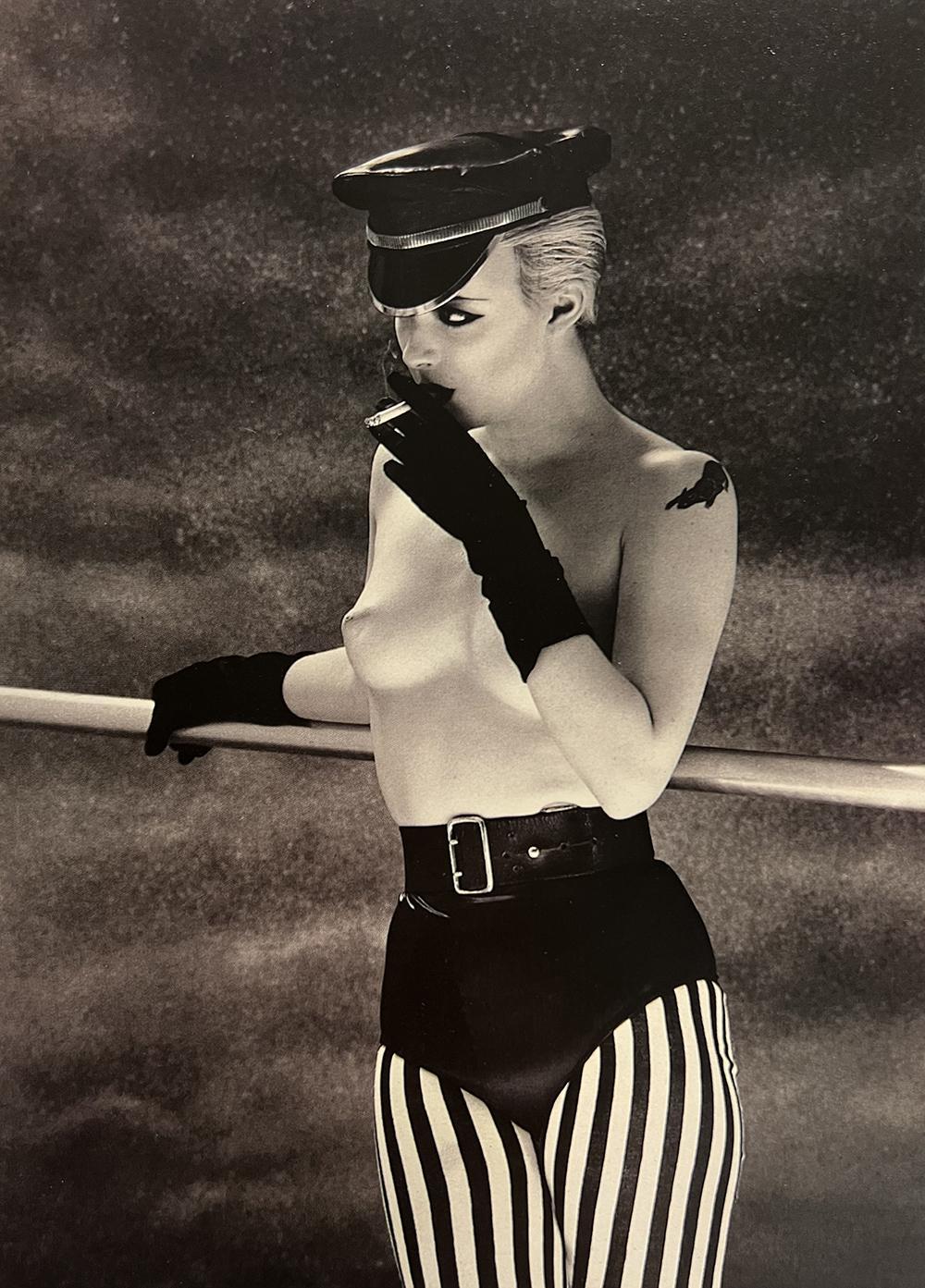

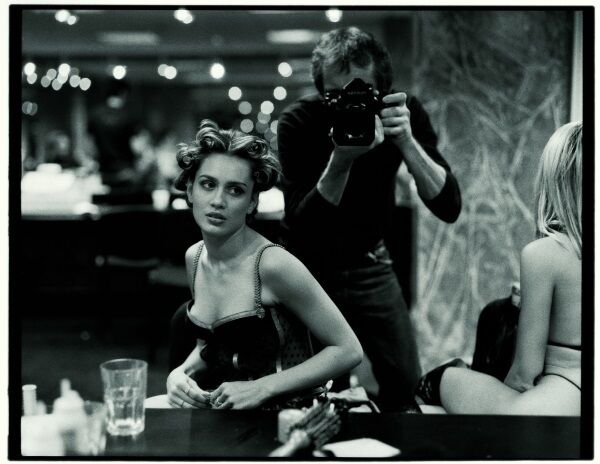

🎭 Iconic Work

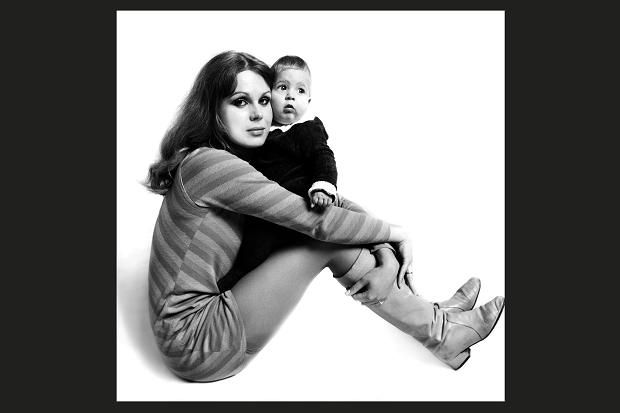

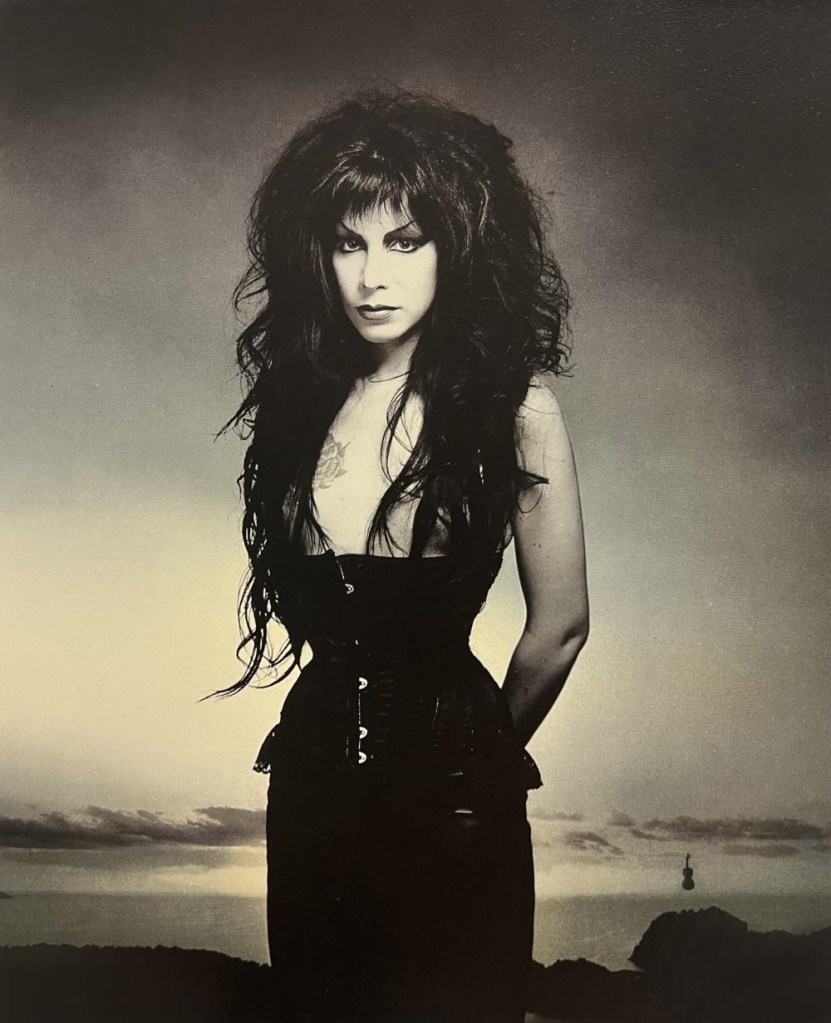

- Pirelli Calendars: Shot three editions (1973, 1974, 1977), known for their bold and sensual imagery.

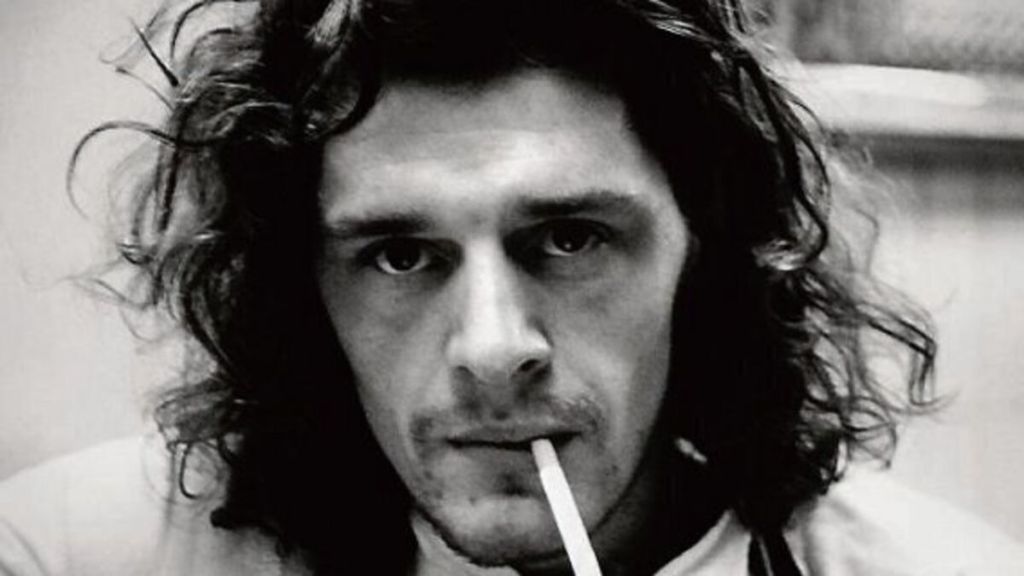

- David Bowie Collaboration: Created the legendary Aladdin Sane album cover (1973), featuring Bowie with the lightning bolt makeup — one of the most iconic images in music history.

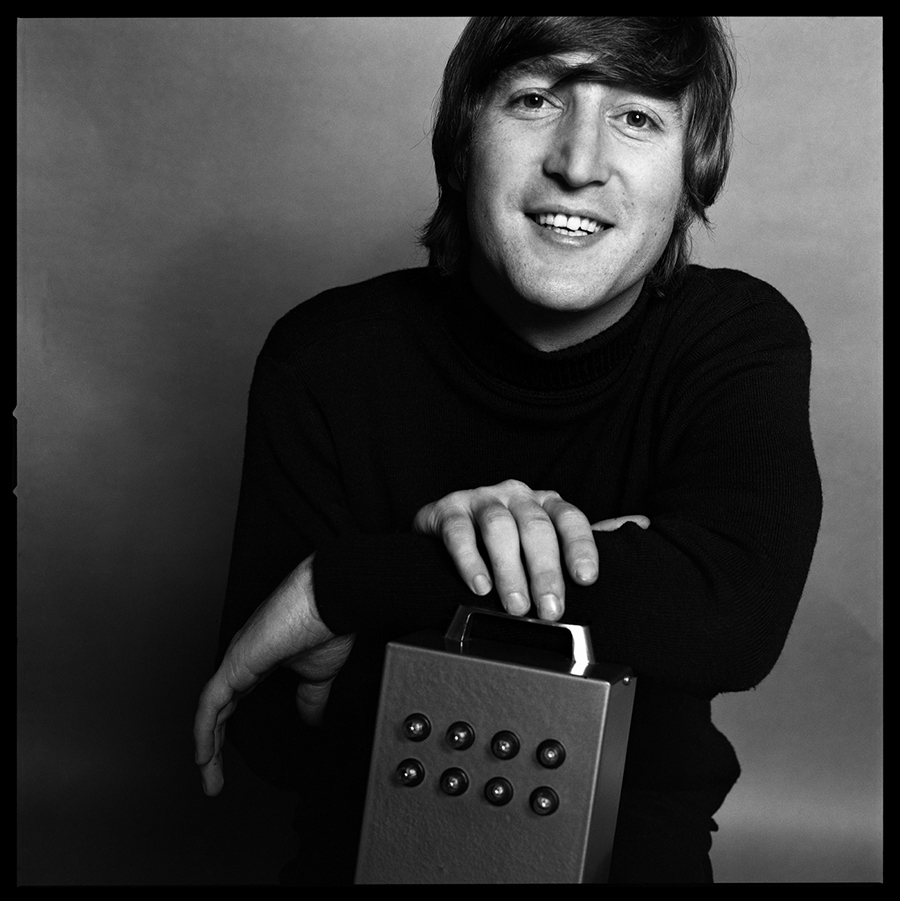

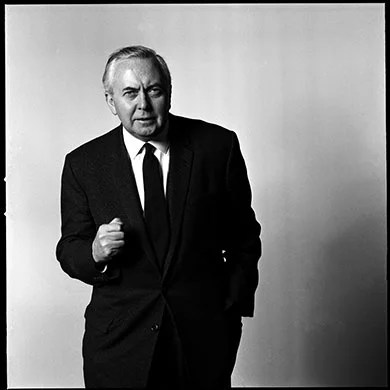

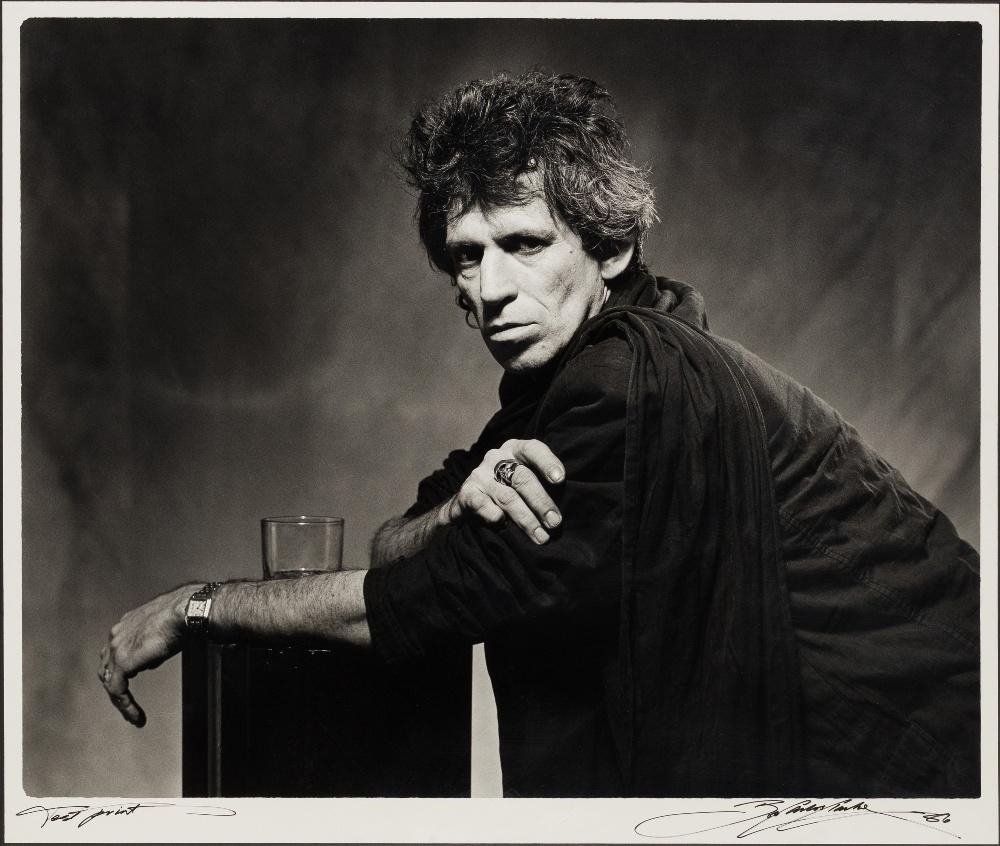

- Celebrity Portraits: Photographed John Lennon, Michael Caine, and Jean Shrimpton, among others.

- His fashion spreads blurred the line between documentary and glamour, emphasizing realism and attitude.

🎬 Other Ventures

- In the 1980s, Duffy stepped back from photography, moving into film production and commercials.

- Later pursued antique furniture restoration, showing his versatility and interest in craftsmanship.

⚰️ Death

- Died: May 31, 2010, at age 76 in London.

- Survived by his children: Christopher, Charlotte, Samantha, and Carey.

🌍 Legacy

- Remembered as one of the most influential photographers of the 20th century.

- His rediscovered archive has been exhibited widely, ensuring his work continues to inspire.

- The “Black Trinity” (Bailey, Donovan, Duffy) are credited with transforming fashion photography into a vibrant, youthful, and culturally relevant art form.

✨ In Summary

Brian Duffy was a revolutionary figure in fashion photography, blending design sensibility with raw energy. His work defined the look of 1960s London, immortalized cultural icons, and left a legacy that continues to shape visual culture today.